This post explores the recurring cycle of ego inflation and collapse as the necessary precondition for genuine individuation. Drawing on Jung and Edinger, it argues that what we interpret as personal failure is often the Self rebuffing our premature attempts at control, forcing us through repeated collisions with reality until every false refuge – pleasure, safety, power, knowledge, belonging – exhausts itself. What remains is the stark necessity of the one path that does not destroy us.

Welcome back.

I have a large ego, even though I don’t have the accomplishments that would typically accompany such a thing. I attribute this partly to being told I was perfect by my mother growing up, and partly to weakness, laziness, timidity – a reluctance to confront the real world.

Ego development itself is not bad. In fact it is necessary, especially in the first part of life. A strong ego gives us the scaffolding to project a persona of extraversion, friendliness, competence, and ambition which society values, to go out into the world and make our mark on it materially. But such an ego is subject to periodic cycles of inflation – when we identify too much with an idea, archetype, or cause – followed by deflation when those hopes inevitably fail1, and reconnection to reality to begin the cycle anew, a little wiser each time. The persona is something we project outwards, while our faith properly belongs elsewhere – to an autonomous psyche (the Self) that most people are not consciously aware of and which our “extraverted as Hell” (per Jung) society does not value much.

Think of the Self as the intuition which arises when one holds competing and irreconcilable opposites (or conflicting duties, or impossible choices) within oneself without resolution, as discussed with here. When I refer to irreconcilable opposites, I mean the kinds of conflicts where every choice violates something essential, and no amount of reasoning can make the pain go away. Examples include loyalty versus truth (protecting someone you love vs. saying what will wound them), autonomy versus obligation (following your own path vs. fulfilling real duties to others), or security versus growth (choosing safety that keeps you stagnant vs. risking the unknown that could break you), but there are an endless number of such opposites. These aren’t abstract dilemmas; they’re situations where each option carries a genuine loss, and the ego cannot manufacture a clean solution, and we all endure these on small and large scales regularly – it is part of being human. Which part of you ultimately makes the decision between such impossible choices? Sure, one may rationalize one decision over another, but the choice is ultimately made within, by unconscious processes one is not aware of. As Jung states,

The real moral problems spring from conflicts of duty. Anyone who is sufficiently humble, or easy-going, can always reach a decision with the help of some outside authority. But one who trusts others as little as himself can never reach a decision at all, unless it is brought about in the manner which Common Law calls an “Act of God”…In all such cases there is an unconscious authority which puts an end to doubt by creating a fait accompli.

The idea here is to consciously hold the tension of opposites until something deeper within us decides on an action, that we remain aware that it is not us egotistically deciding but something within and that we are listening to that response. Holding the pain unresolved between opposites until the answer emerges within is what Jung called the transcendent function (which relates to the essence of the Mystery religions). One may, of course, think of this emerging decider from the unconscious as resulting either from one’s biological processes or from the will of God, but the latter is psychologically healthier: “If…the inner authority is conceived as the “will of God”…our self-esteem is benefitted because the decision then appears to be an act of obedience and the result of a divine intention.” As Edinger states:

If a mistake is made by the young, it is proper that they take responsibility for it. For someone in the second half of life, a mistake is properly understood as an act of God, and this is how I think one should understand so-called mistakes in analytic work with patients. They are meaningful acts of God, and in that sense they are not quite mistakes at all; they are interventions from the unconscious that have a purposefulness still to be discovered.

The intuition from the transcendent function is something one receives, it isn’t something one chooses, it is mysterious how such intuition arrives to us and it is often surprising. Furthermore, such intuition morphs under observation much like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle so it cannot be controlled (by us, by others, or by our nefarious elites).

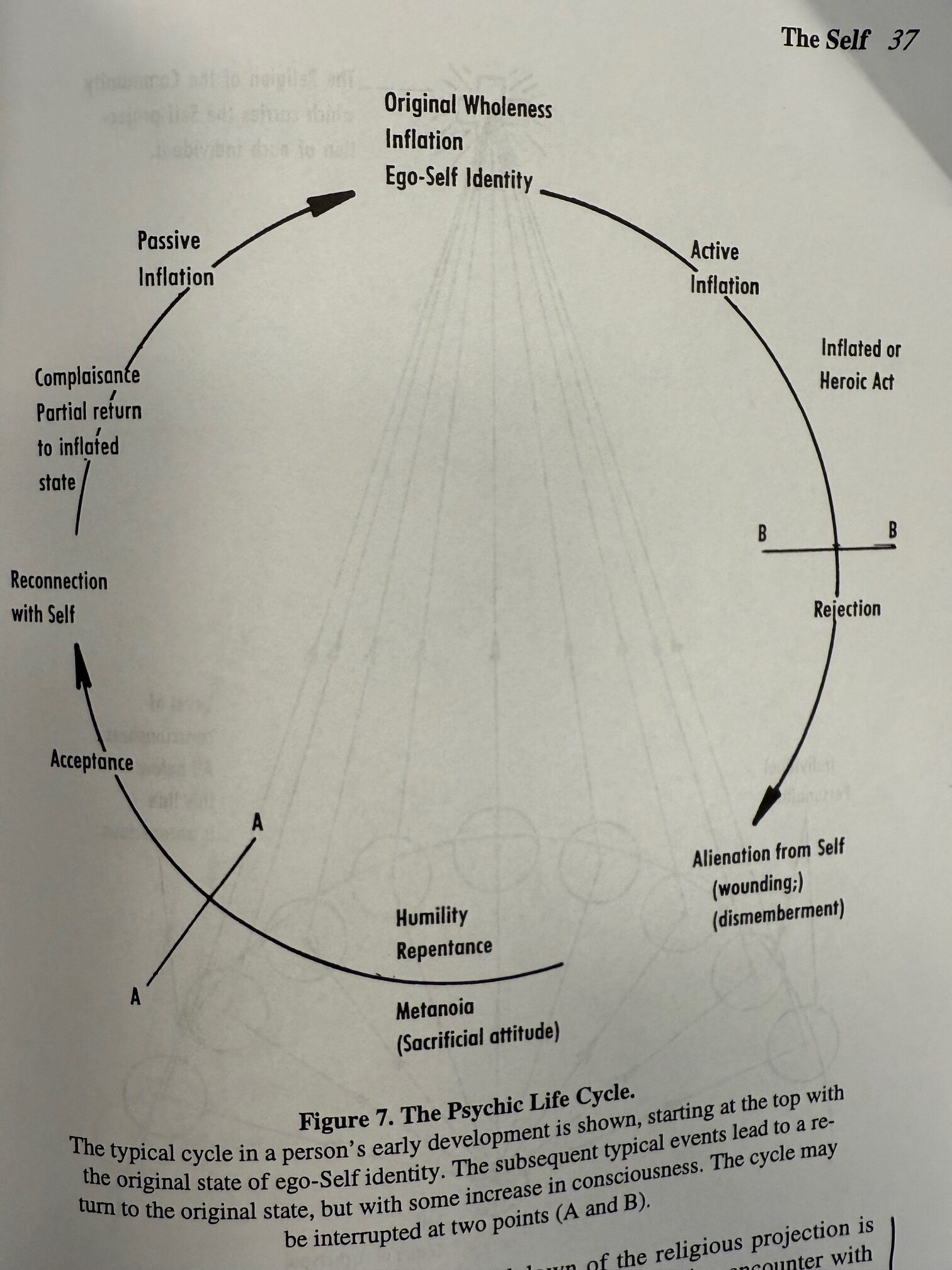

The alternative approach involves overriding one’s intuition and forcing an ego-choice, which prematurely resolves the crucifixion of opposites into one polarity. This is very understandable to do, because sitting unresolved between the opposites consciously is very painful. Inflation often results, where one identifies with the polarity or archetype chosen.2 Inflation always plays out the same way: the ego swells with identification with the polarity, eventually collides with reality – that the ego is not actually worthy of the accolades heaped upon it by the individual – and then collapses in humiliation where, after a pause, it swells again and the process begins anew. Jung saw this cycle – inflation and crash, inflation and crash – as unavoidable, until finally, usually in the liminal period of mid-life (discussed previously here), one learns the hard lesson, gains elements of humility, and learns to resist the polarities. This is the cycle:

It is easy to treat each cycle of inflation and crash as a moral weakness, and I still do this today, as if I could have avoided it if only I were strong enough. This is due to our Western cultural and religious backgrounds, which treats every action as intrinsically black-and-white, right and wrong, good and evil, and not as an avenue toward deeper growth. Recently my Self asked me to commit to a course of withdrawal/deprivation, which I accepted, but then faltered when the expected “benefit” was scattered and inconsistent. I beat myself up for weakness of action and moral failure. It happened again recently (as a small example) with a stupid free-to-play, pay-to-win video game.3 But from another perspective, these failures are the setup for a deepening relation to the Self, where each detour, each bargain, each attempt to force a quid pro quo eventually burns itself out, fails to deliver, and drives one back toward the Self. The thing is that this must be experienced as a lived reality, it cannot be absorbed merely intellectually; the intellect is but one part of the journey to knowledge, the other part of it is lived phenomenological resonance and experience. This is why someone older and wiser may give a younger man advice but he usually won’t listen; one often needs to go through the experience himself, to understand the correctness or wrongness of an action or path in one’s own way (although having the right guide may help). And this is natural! When I see someone younger in ego inflation, I empathize with him or her; it is a process that one must go through, it is a stage of development.

Edinger explains this process in The Aion Lectures, where he states:

As long as the [unconscious ego-Self identity] is not acted upon, nothing happens, but if it is expressed in action it meets a rebuff from reality. That rebuff causes a wounding and reflection, then a metanoia or change of mind, which heals the wound and reconnects the ego with the Self, returning it to its state of ego-Self identity until the next episode. Each time that circle is made, a little bit of ego-Self identity is dissolved, so to speak, and a little more consciousness is born.

Religion or identity can serve as an ego-protective mechanism that shields one from access to the Self, at least until that identity breaks down:

If that projection breaks down, various things can happen: one can lose one’s connection to the Self and fall into a state of alienation and despair because life becomes meaningless. Or one can fall into an inflation, which very often leads to alienation, its opposite. Or the Self may be reprojected – for instance onto a political system, a common phenomenon. The meanings that used to be carried by religious contents are now often carried by political movements.4

A fourth possibility following the breakdown of the religious projection is that individuation can occur, in which case the ego has a living encounter with the Self as a psychological entity.

Under this paradigm, the faltering is not a sin but part of the circumambulation around the center of the Self. The path is a spiral: weaving, backtracking, approaching indirectly, where failure is data that another road is dead. It is a lifelong process with no endpoint; the center is never reached, merely approached. Visually, it looks like a mandala, the structure of which Jung heavily focused on throughout his life. Here’s an example:

The Self does not negotiate – it waits, and every false ego bargain collapses sooner or later. This is why following it cannot be understood as initiation in the sense of sacrifice for reward. It corners you through repeated failure; it does not bribe you into compliance. One follows it because every other road leads to death and unfulfillment. Faith here is the residue of exhaustion, proof that every other option corrodes; hints at our path are found in what we are naturally drawn towards.5

This is, of course, a hard pill to swallow. Freedom in this sense is the opposite of the modern understanding as infinite choice: it is actually the grim necessity of consenting to the only path that does not annihilate you. In Jung’s darker register, individuation is not the romantic “become who you are” but the recognition that refusing to become who you are sickens and kills you.

Let’s explore this concept with a parable. A traveler enters a land of branching roads. Each road is wide and brightly marked, promising what every heart craves: Pleasure, Safety, Power, Knowledge, Belonging.

He sets out upon them one by one.

- On the Pleasure road, feasts and lovers await. For a time, he believes he has found joy. Then a plague sweeps through, and he sees how fragile pleasure is when bodies decay. The banquet hall empties, and he walks back to the crossroads alone.

- On the Safety road, walls rise around him, guards patrol, rules are posted at every corner. At first he feels secure. Then betrayal comes: the guards turn their spears inward, the rules multiply until he cannot breathe. His prison was built from his own longing. He flees back to the crossroads.

- On the Power road, he ascends quickly: wealth, allies, a throne. Yet when deprivation strikes the land – famine, drought – he sees his power hollowed, for no command can conjure bread from dust. The people curse him, and he stumbles back broken.

- On the Knowledge road, libraries stretch to the horizon. He reads without ceasing. But when confusion descends, each scroll cancels the next, until he cannot tell truth from falsehood. He is buried beneath contradictions, crawling out blind and weary.

- On the Belonging road, he finds a crowd singing in unison. He feels lifted, carried. But when war comes, the same voices that embraced him turn against outsiders, then against each other. He loses his name, his self, his song. With a torn throat, he returns again.

Each return is more shameful, more exhausting. The traveler feels mocked by his own failures. But the shame itself is revelation: he now knows these roads cannot bear the weight of existence. At last he sees the narrow path he had always ignored – unmarked, silent, offering nothing. He takes it not from faith, not from hope, but because all the other ways have already killed him.

As he walks, stripped of illusions, he begins to sense a strange paradox: though the path is barren, he is less afraid. No plague, betrayal, deprivation, confusion, or war can harm him as they once did because he no longer leans on false signs. This path has no promise, but it cannot be broken. And so he continues, not as a hero chasing glory, but as one compelled – free only because he has no choice left.

This is the compulsory pilgrimage through stress tests: each crisis destroys a false refuge until only the path of the Self remains.

This parable is in line with existing traditions. Think of Augustine’s Confessions: he tries lust, ambition, philosophy, and finds all paths empty until finally turning to God. He doesn’t frame the detours as wasted, but as necessary proofs of insufficiency. In the Pali Buddhist canon, samsara is often described as exhausting, repetitive failure: lifetime after lifetime of desire, disappointment, sickness, death. The “shame” of failing is expected. Enlightenment doesn’t come as a heroic initiation reward but as finally seeing that no other option works. In Stoicism (which I will cover in a future post) Epictetus is blunt: you can rebel against necessity if you like, but you’ll only exhaust yourself. The discipline is to align with what cannot be otherwise. Failures are reminders that you still want things to be other than they are.

In this view, faith isn’t blind the way we typically think of it today; rather, it is earned as the residue of repeated stress tests, each one demonstrating the futility of all other options. Over time, the shame of “failing” gives way to inevitability: you can no longer deny that only one path is viable, because all the others have collapsed under trial. And when we listen to the Self, we may, ultimately, help bring consciousness to God himself.

Thanks for reading.

Subscribe:

Email delivery remains on Substack for now.

1 These hopes always fail, even if one is successful; this is because nothing lasts forever, we are finite and limited beings, and even if we succeed success is met with boredom until a new object of striving is chosen and the process repeats unless one hits limitation (even if it limitations caused by health issues later in life). There is no way of avoiding this; the wall always approaches. “My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair! No thing beside remains. Round the decay / Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare / The lone and level sands stretch far away.” This post on philosophical pessimism delves into this concept further.

2 Jung defined archetypes as universal symbols and patterns that influence human behavior and personality. They are innate patterns of thought and behavior that strive for realization within an individual’s environment, playing a crucial role in the development of one’s unique identity. Examples of archetypes include the Innocent, the Orphan, the Hero, the caregiver, the Explorer, the Rebel, the Lover, the Creator, the Jester, the Sage, the Magician, the Ruler.

3 The psychology of this was very interesting. The iPhone game, Zombie Waves, sucks one in with free play; then the user needs to pay to avoid advertisements and advance faster than the competition. It is basically a hack of the will-to-power, monetizing it for its owners financial gain. I knew this as I was paying, knew I was being stupid, of course, yet I still paid and played. There appears to have been a lot of science, research, and intent behind the way they structured this game, and the same approach is used in a lot of other games, including games marketed toward children. The owners of this particular game appear opaque, and it is popular (over 200,000 followers on the Facebook group for it). I finally kicked the addiction when I realized with horror how much I had spent (small in the grand scheme of things, but ridiculous for an iPhone app), thought about how much better uses I would have had for the money, and deleted it, hopefully permanently (another issue is that the game is connected via cloud and tied into your Apple profile, so it’s impossible or close to impossible to delete it permanently – I had deleted the game multiple times in the past). My intuition had told me not to play this game and I didn’t listen to it, paying a price not just of money but also of time and mental agitation, but hopefully learning a lesson somewhere from it – perhaps the lesson was how it hijacked my risk/reward circuitry and made a fool out of me so I am more prepared to avoid similar actions in the future.

4 Hence the commonality of the red pill and black pill among the right: one takes the red pill to become a “based right wing populist”, then when that doesn’t work out (with Trump compromising with and then becoming subservient to the establishment), one may shift to the blackpill, i.e. a collapse into defeatism and nihilism, which is an improper way of living life. One identifies with these movements and positions, which is improper ego identification.

5 Per Edinger: “When one is in touch with the Self, the libido connection that is generated has the effect of locating the scattered fragments of one’s identity that reside in the world. In reading and in daily encounters with people and events in the world, one can identify what belongs to oneself by noticing one’s reactions. One values what belongs to oneself, one has an “ah ha” experience – oh, that’s something significant! Reading and going through the world with that awareness, one can constantly pick up things that belong to oneself….It gives one a kind of magnetic power by which one can attract and integrate pieces of one’s identity.”